Yamcha and Existentialism

Yamcha—the constantly defeated character, proven time and again the weakest in a line of vastly powerful fighters—marches to his fate regardless with zeal and a burning commitment.

Something about Yamcha from Dragon Ball captivates my mind.

About a month ago, I joined my first 10K fun run. I was wholly unprepared for it, having only run 5K at most prior, and barely even managing to do that just 2 days before the event. But I was challenged by my wife who had already run a 10K, and who's really good at running in a way that I'm not and probably never will be. Long story short, I ran anyway and actually finished the race, but with extreme difficulty and agony. In fact, it was the most excruciating thing I've ever experienced; just pain every single step that felt as if it wouldn't ever end. But overcoming pain yields pride, and completing that race and showing our daughter back home my medal was one of the proudest moments of my life.

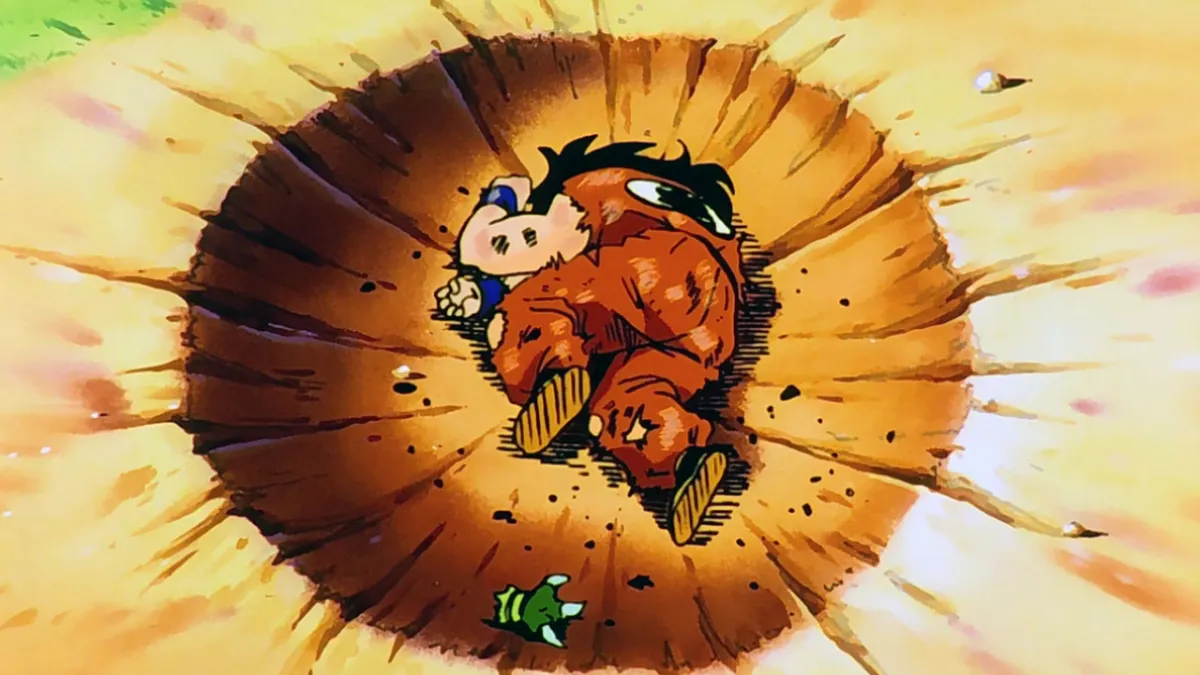

In the morning of the fun run, knowing I was going to subject myself to a miserable experience that I was going to do anyway because of some twisted sense of pride and determination, I was reminded of Yamcha. I shared a picture of him on Facebook in his iconic death pose, curled up in a crater after a Saibaman blew him up. I captioned it: "Today, we meet our fate—like Yamcha."

Looking back at it now, I wasn't actually poking fun at Yamcha but was looking to him as a source of strength at that moment when I was almost sure I wouldn't finish the race.

And as I go through my philosophical readings, I've realized something fascinating about this character: Yamcha is the ultimate figure of existentialism.

Which is why I'm taking a break from more serious discussions about life and digital marketing to exercise a bit of fun philosophy about this character Dragon Ball fans love to mock.

Yamcha: A History of Utter Defeat

In Dragon Ball, Yamcha starts out as a simple desert bandit who wanted to steal Goku and Bulma's Dragon Balls. He later befriended the group, trained under Master Roshi, and joined martial arts tournaments. His results competing in the World Martial Arts Tournaments (Tenkaichi Budokai) were less than stellar:

- 21st Budokai: Lost to Jackie Chun (Master Roshi in disguise)

- 22nd Budokai: Lost to Tien Shinhan

- 23rd Budokai: Faced Kami (in disguise as Hero) and lost

Make no mistake—Yamcha was a great martial artist and much stronger than base-level humans like Mr. Satan, but it's clear he's just in the bottom tier of serious fighters in the Dragon Ball universe.

None of these losses seemed to have deterred Yamcha from practicing his craft, however. As many would recall, in the Saiyan Saga, together with Earth's mightiest warriors, he fought Saibamen—fierce alien fighters grown from seeds planted by Nappa on Vegeta's orders. He almost defeated one but turned his back on the green creature; it then jumped up, latched itself onto him and self-destructed, killing Yamcha instantly (who would of course be later revived as is Dragon Ball tradition).

Surely, Yamcha must have known the odds were always against him, even if he didn't actually witness how strong Vegeta and Nappa were before his death? He had lost multiple times in Earth tournaments before, and the Saibamen were already on par with Raditz, a Saiyan who defeated Goku and Piccolo before dying. Goku and Piccolo, of course, were the strongest of Earth's heroes. The Saibamen were clearly just minor henchmen of the invading Saiyans who were of a different, much powerful extraterrestrial species.

But Yamcha's propensity to put himself out there despite the obvious power gap between him and his opponents didn't end there.

During the Android/Cell saga, he was part of the team that actively searched for the Androids—vicious killing machines who Trunks (from the future) warned them would wipe out all Z fighters, including Yamcha. Nevertheless, facing the almost definite possibility that he will die a second time, Yamcha went looking for the threat, got attacked by Android 20, and was pierced through his chest, rescued only by Krillin and healed by a Senzu bean.

But none of these defeats in fighting were probably as devastating and as brutal as losing Bulma—his original love interest in the first series—to Vegeta, the invading alien prince who was ultimately responsible for his death.

As everyone knows, Vegeta would later join the Earth's forces, and Yamcha would even fight alongside this person who basically sealed his utter defeat in fighting and in love.

All these had made Yamcha the butt of jokes both in-universe by the characters, and by many Dragon Ball fans. He's now more or less just a recurring punchline for power scaling jokes; a footnote in the grand saga of planet-shattering beings fighting for control of the universe.

But now we've summarized his role in the Dragon Ball franchise, I want to go back to my original proposal: put under a philosophical microscope, Yamcha stands out as more than just comic relief and a symbol of certain defeat; on the contrary, he is the ultimate existential hero and a master of overcoming.

Yamcha as Camus' Absurd Man

In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus talks about the "absurd," which arises from the conflict between human beings' search for meaning and the silent, indifferent universe.

"It is that divorce between the mind that desires and the world that disappoints, my nostalgia for unity, this fragmented universe and the contradiction that binds them together." — Albert Camus

In this philosophical essay, Camus likens human beings' metaphysical situation to that of the Greek mythological figure, Sisyphus, who was condemned to roll a boulder uphill for all eternity, only for it to roll back down. His task was essentially meaningless, and paints a picture of the absurd.

People innately strive for meaning in an existence that consistently proves its meaninglessness and the utter futility of their efforts. They nevertheless find ways to cope with the tragic situation through religion, ideology, or by subscribing to some other belief system that keeps them going by promising them an eventual payoff. Thus, for example, you may believe that doing charity in this life is worth it despite evidence to the contrary, because your religion tells you that you will be rewarded in the afterlife.

But the absurd man recognizes the pointlessness of it all without succumbing to illusions or false hopes. The absurd man chooses to live fully and passionately despite the fruitlessness of everything. Camus calls this "revolt."

It is a constant confrontation between man and his own obscurity. It is an insistence upon an impossible transparency... It is not aspiration, for it is devoid of hope. That revolt is the certainty of a crushing fate, without the resignation that ought to accompany it. — Albert Camus

Despite his eternal punishment to roll a boulder that goes nowhere, Camus posits that Sisyphus is happy. "The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy," he says.

Isn't this fundamentally how Yamcha lives his life?

Yamcha—the constantly defeated character, proven time and again the weakest in a line of vastly powerful fighters—marches to his fate regardless with zeal and a burning commitment.

In the face of nigh unstoppable forces and fully aware of his fragility and inferior skill, he nevertheless fights them to the death. Robbed of his love and a bright future by a man he couldn't hope to even scratch and who, moreover, extinguished his very life, staring down the barrel of total existential embarrassment, he forges on—cheering the same man like a fool.

For Yamcha, every instance of combat or confrontation is certain failure, obliteration, and a source of universe-crossing ridicule, but be that as it may, he embraces it, and treats it as a means of revolt against a destiny already mapped out for him.

Yamcha is nothing less than Camus' absurd man.

He may have no freedom both in the sense that he is powerless against galactic forces, and in the way that Dragon Ball writers have already relegated him to the role of the franchise's clown, but Yamcha lives without appeal and in his own terms nevertheless. He is, in Camus' terms, the quintessential "conqueror" or "warrior" who chooses action over hope and doesn't seek absolute justice.

In Camus' version of existentialist philosophy, this is how human beings can coexist with the seeming meaninglessness of existence. It is a supremely noble effort, one that gods would even envy.

In Jean-Paul Sartre's existentialism, this is also how somebody can start building meaning from nothing. Facing nihilism and hopelessness, one can still construct a meaningful life by choosing to act and commit, and being responsible for their own actions.

Who knows—maybe Yamcha fought for something greater in his own mind than the survival of his friends? After all, fighting for your loved ones seems like a foolish errand when you are guaranteed to die every single time. Perhaps Yamcha was creating his own meaning and narrative through his own doomed struggle.

In Nietzschean philosophy, Yamcha's actions may also be viewed as self-overcoming.

“The noble human being honors in himself the powerful one, him who has power also over himself... who takes pleasure in subjecting himself to severity and hardness, and has reverence for all that is severe and hard.” — Nietzsche

Self-overcoming is constant self-transformation to oppose stagnation in identities and ideologies, especially self-denying ones. It is an expression of the will to power, a natural and metaphysical force that runs through human beings and the universe, and strives to expand, to dominate, not just to survive.

Yamcha doesn't train to survive or win hopeless battles. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, he won't. He only trains to get stronger every day, no matter how insignificant the gains are in the context of infinite power scaling, and again, no matter the assured outcome of such fights.

He transforms himself just because it is his will to grow stronger. Nothing else.

Yamcha similarly doesn't reproach Bulma, Vegeta, or anyone else, not even the cosmos, for what he is or has become. He is without resentment. His passion for living and fighting is an excellent demonstration of Nietzsche's concept of amor fati—love of one's fate, saying "yes" to all life, even the ugliest and most insufferable parts of it.

Yamcha lives the absurd and thrives in it.

Yamcha as the Ultimate Dragon Ball Hero

Everyone loves Goku, sure. But Goku is Goku. We all know he's going to win. If he loses, he will win eventually, somehow. He's the protagonist, the main character.

But who in real life can say for certain they are the main character and is protected by the plot? Nobody.

In our daily lives, defeat is almost always as certain as a win. In fact, in many cases, a total collapse of all our carefully crafted plans is just waiting around a corner to latch onto us and explode, like a damned Saibaman. Knock on wood.

In this way, Yamcha is the ultimate Dragon Ball hero, not Goku. Neither is Krillin, the other notable human Z fighter, because he's Goku's best friend and by extension is shielded by the plot (as evidenced by his great fortune in the story).

In this life where we are always the underdogs rebelling against forces growing more merciless every moment, where it's increasingly hard to believe in anything true or pure that serves a greater purpose, but where we must nevertheless continue to struggle despite grim-looking results, Yamcha should stand among the greatest of our fictional heroes.

Why? Because he shows us that even if we fail, beauty lies in the act of resistance itself—an iconic scene of noble rebellion; a wounded, broken, smoking hero lying in a huge crater.

And if you win, well, victory is that much sweeter having proven everyone wrong.

So in this house, we don't say Kamehameha. We say Wolf Fang Fist!